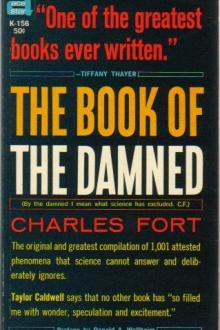

The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned, Charles Fort [best ereader for academics txt] 📗». Author Charles Fort

Of course it is our acceptance that these masses not only accompanied tornadoes, but were brought down to this earth by tornadoes.

Flammarion, The Atmosphere, p. 34:

Block of ice, weighing four and a half pounds that fell at Cazorta, Spain, June 15, 1829; block of ice, weighing eleven pounds, at Cette, France, October, 1844; mass of ice three feet long, three feet wide, and more than two feet thick, that fell, in a storm, in Hungary, May 8, 1802.

Scientific American, 47-119:

That, according to the Salina Journal, a mass of ice weighing about 80 pounds had fallen from the sky, near Salina, Kansas, August, 1882. We are told that Mr. W.J. Hagler, the North Santa Fé merchant became possessor of it, and packed it in sawdust in his store.

London Times, April 7, 1860:

That, upon the 16th of March, 1860, in a snowstorm, in Upper Wasdale, blocks of ice, so large that at a distance they looked like a flock of sheep, had fallen.

Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1851-32:

That a mass of ice about a cubic yard in size had fallen at Candeish, India, 1828.

Against these data, though, so far as I know, so many of them have never been assembled together before, there is a silence upon the part of scientific men that is unusual. Our Super-Sargasso Sea may not be an unavoidable conclusion, but arrival upon this earth of ice from external regions does seem to be—except that there must be, be it ever so faint, a merger. It is in the notion that these masses of ice are only congealed hailstones. We have data against this notion, as applied to all our instances, but the explanation has been offered, and, it seems to me, may apply in some instances. In the Bull. Soc. Astro. de France, 20-245, it is said of blocks of ice the size of decanters that had fallen at Tunis that they were only masses of congealed hailstones.

London Times, Aug. 4, 1857.

That a block of ice, described as "pure" ice, weighing 25 pounds, had been found in the meadow of Mr. Warner, of Cricklewood. There had been a storm the day before. As in some of our other instances, no one had seen this object fall from the sky. It was found after the storm: that's all that can be said about it.

Letter from Capt. Blakiston, communicated by Gen. Sabine, to the Royal Society (London Roy. Soc. Proc., 10-468):

That, Jan. 14, 1860, in a thunderstorm, pieces of ice had fallen upon Capt. Blakiston's vessel—that it was not hail. "It was not hail, but irregular-shaped pieces of solid ice of different dimensions, up to the size of half a brick."

According to the Advertiser-Scotsman, quoted by the Edinburgh New Philosophical Magazine, 47-371, an irregular-shaped mass of ice fell at Ord, Scotland, August, 1849, after "an extraordinary peal of thunder."

It is said that this was homogeneous ice, except in a small part, which looked like congealed hailstones.

The mass was about 20 feet in circumference.

The story, as told in the London Times, Aug. 14, 1849, is that, upon the evening of the 13th of August, 1849, after a loud peal of thunder, a mass of ice said to have been 20 feet in circumference, had fallen upon the estate of Mr. Moffat, of Balvullich, Ross-shire. It is said that this object fell alone, or without hailstones.

Altogether, though it is not so strong for the Super-Sargasso Sea, I think this is one of our best expressions upon external origins. That large blocks of ice could form in the moisture of this earth's atmosphere is about as likely as that blocks of stone could form in a dust whirl. Of course, if ice or water comes to this earth from external sources, we think of at least minute organisms in it, and on, with our data, to frogs, fishes; on to anything that's thinkable, coming from external sources. It's of great importance to us to accept that large lumps of ice have fallen from the sky, but what we desire most—perhaps because of our interest in its archaeologic and palaeontologic treasures—is now to be through with tentativeness and probation, and to take the Super-Sargasso Sea into full acceptance in our more advanced fold of the chosen of this twentieth century.

In the Report of the British Association, 1855-37, it is said that, at Poorhundur, India, Dec. 11, 1854, flat pieces of ice, many of them weighing several pounds—each, I suppose—had fallen from the sky. They are described as "large ice-flakes."

Vast fields of ice in the Super-Arctic regions, or strata, of the Super-Sargasso Sea. When they break up, their fragments are flake-like. In our acceptance, there are aerial ice-fields that are remote from this earth; that break up, fragments grinding against one another, rolling in vapor and water, of different constituency in different regions, forming slowly as stratified hailstones—but that there are ice-fields near this earth, that break up into just such flat pieces of ice as cover any pond or river when ice of a pond or river is broken, and are sometimes soon precipitated to the earth, in this familiar flat formation.

Symons' Met. Mag., 43-154:

A correspondent writes that, at Braemar, July 2, 1908, when the sky was clear overhead, and the sun shining, flat pieces of ice fell—from somewhere. The sun was shining, but something was going on somewhere: thunder was heard.

Until I saw the reproduction of a photograph in the Scientific American, Feb. 21, 1914, I had supposed that these ice-fields must be, say, at least ten or twenty miles away from this earth, and invisible, to terrestrial observers, except as the blurs that have so often been reported by astronomers and meteorologists. The photograph published by the Scientific American is of an aggregation supposed to be clouds, presumably not very high, so clearly detailed are they. The writer says that they looked to him like "a field of broken ice." Beneath is a picture of a conventional field of ice, floating ordinarily in water. The resemblance between the two pictures is striking—nevertheless, it seems to me incredible that the first of the photographs could be of an aerial ice-field, or that gravitation could cease to act at only a mile or so from this earth's surface—

Unless:

The exceptional: the flux and vagary of all things.

Or that normally this earth's gravitation extends, say, ten or fifteen miles outward—but that gravitation must be rhythmic.

Of course, in the pseudo-formulas of astronomers, gravitation as a fixed quantity is essential. Accept that gravitation is a variable force, and astronomers deflate, with a perceptible hissing sound, into the punctured condition of economists, biologists, meteorologists, and all the others of the humbler divinities, who can admittedly offer only insecure approximations.

We refer all who would not like to hear the hiss of escaping arrogance, to Herbert Spencer's chapters upon the rhythm of all phenomena.

If everything else—light from the stars, heat from the sun, the winds and the tides; forms and colors and sizes of animals; demands and supplies and prices; political opinions and chemic reactions and religious doctrines and magnetic intensities and the ticking of clocks; and arrival and departure of the seasons—if everything else is variable, we accept that the notion of gravitation as fixed and formulable is only another attempted positivism, doomed, like all other illusions of realness in quasi-existence. So it is intermediatism to accept that, though gravitation may approximate higher to invariability than do the winds, for instance, it must be somewhere between the Absolutes of Stability and Instability. Here then we are not much impressed with the opposition of physicists and astronomers, fearing, a little mournfully, that their language is of expiring sibilations.

So then the fields of ice in the sky, and that, though usually so far away as to be mere blurs, at times they come close enough to be seen in detail. For description of what I call a "blur," see Pop. Sci. News, February, 1884—sky, in general, unusually clear, but, near the sun, "a white, slightly curdled haze, which was dazzlingly bright."

We accept that sometimes fields of ice pass between the sun and the earth: that many strata of ice, or very thick fields of ice, or superimposed fields would obscure the sun—that there have been occasions when the sun was eclipsed by fields of ice:

Flammarion, The Atmosphere, p. 394:

That a profound darkness came upon the city of Brussels, June 18, 1839:

There fell flat pieces of ice, an inch long.

Intense darkness at Aitkin, Minn., April 2, 1889: sand and "solid chunks of ice" reported to have fallen (Science, April 19, 1889).

In Symons' Meteorological Magazine, 32-172, are outlined rough-edged but smooth-surfaced pieces of ice that fell at Manassas, Virginia, Aug. 10, 1897. They look as much like the roughly broken fragments of a smooth sheet of ice—as ever have roughly broken fragments of a smooth sheet of ice looked. About two inches across, and one inch thick. In Cosmos, 3-116, it is said that, at Rouen, July 5, 1853, fell irregular-shaped pieces of ice, about the size of a hand, described as looking as if all had been broken from one enormous block of ice. That, I think, was an aerial iceberg. In the awful density, or almost absolute stupidity of the 19th century, it never occurred to anybody to look for traces of polar bears or of seals upon these fragments.

Of course, seeing what we want to see, having been able to gather these data only because they are in agreement with notions formed in advance, we are not so respectful to our own notions as to a similar impression forced upon an observer who had no theory or acceptance to support. In general, our prejudices see and our prejudices investigate, but this should not be taken as an absolute.

Monthly Weather Review, July, 1894:

That, from the Weather Bureau, of Portland, Oregon, a tornado, of June 3, 1894, was reported.

Fragments of ice fell from the sky.

They averaged three to four inches square, and about an inch thick. In length and breadth they had the smooth surfaces required by our acceptance: and, according to the writer in the Review, "gave the impression of a vast field of ice suspended in the atmosphere, and suddenly broken into fragments about the size of the palm of the hand."

This datum, profoundly of what we used to call the "damned," or before we could no longer accept judgment, or cut and dried condemnation by infants, turtles, and lambs, was copied—but without comment—in the Scientific American, 71-371.

Our theology is something like this:

Of course we ought to be damned—but we revolt against adjudication by infants, turtles, and lambs.

We now come to some remarkable data in a rather difficult department of super-geography. Vast fields of aerial ice. There's a lesson to me in the treachery of the imaginable. Most of our opposition is in the clearness with which the conventional, but impossible, becomes the imaginable, and then the resistant to modifications. After it had become the conventional with me, I conceived clearly of vast sheets of ice, a few miles above this earth—then the shining of the sun, and the ice partly melting—that note upon the ice that fell at Derby—water trickling and forming icicles upon the lower surface of

Comments (0)