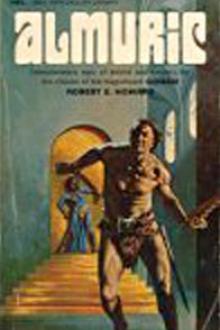

Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Robert E. Howard

- Performer: -

Book online «Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗». Author Robert E. Howard

a dazed impression that it was huge, supple, and catlike. I rolled

frantically aside as it spat and struck at me sidewise; then it was on

me, and even as I felt its claws tear agonizingly into my flesh, the

ice-cold water engulfed us both. A catlike yowl rose half strangled,

as if the yowler had swallowed a large amount of water. There was a

great splashing and thrashing about me; then as I rose to the surface,

I saw a long, bedraggled shape disappearing around the bushes near the

cliffs. What it was I could not say, but it looked more like a leopard

than anything else, though it was bigger than any leopard I had ever

seen.

Scanning the shore carefully, I saw no other enemy, and crawled out

of the pool, shivering from my icy plunge. My poniard was still in its

scabbard. I had had no time to draw it, which was just as well. If I

had not rolled into the pool, just when I did, dragging my attacker

with me, it would have been my finish. Evidently the beast had a true

catlike distaste for water.

I found that I had a deep gash in my thigh and four lesser abrasions

on my shoulder, where a great talon-armed paw had closed. The gash in

my leg was pouring blood, and I thrust the limb deep into the icy

pool, swearing at the excruciating sting of the cold water on the raw

flesh. My leg was nearly numb when the bleeding ceased.

I now found myself in a quandary. I was hungry, night was coming on,

there was no telling when the leopard-beast might return, or another

predatory animal attack me; more than that, I was wounded. Civilized

man is soft and easily disabled. I had a wound such as would be

considered, among civilized people, ample reason for weeks of an

invalid’s existence. Strong and rugged as I was, according to Earth

standards, I despaired when I surveyed the wound, and wondered how I

was to treat it. The matter was quickly taken out of my hands.

I had started across the valley toward the cliffs, hoping I might

find a cave there, for the nip of the air warned me that the night

would not be as warm as the day, when a hellish clamor up near the

mouth of the valley caused me to wheel and glare in that direction.

Over the ridge came what I thought to be a pack of hyenas, except for

their noise, which was more infernal than an Earthly hyena, even,

could produce. I had no illusions as to their purpose. It was I they

were after.

Necessity recognizes few limitations. An instant before I had been

limping painfully and slowly. Now I set out on a mad race for the

cliff as if I were fresh and unwounded. With every step a spasm of

agony shot along my thigh, and the wound, bleeding afresh, spurted

red, but I gritted my teeth and increased my efforts.

My pursuers gave tongue and raced after me with such appalling speed

that I had almost given up hope of reaching the trees beneath the

cliffs before they pulled me down. They were snapping at my heels when

I lurched into the low stunted growths, and swarmed up the spreading

branches with a gasp of relief. But to my horror the hyenas climbed

after me! A desperate downward glance showed me that they were not

true hyenas; they differed from the breed I had known just as

everything on Almuric differed subtly from its nearest counterpart on

Earth. These beasts had curving catlike claws, and their bodily

structure was catlike enough to allow them to climb as well as a lynx.

Despairingly, I was about to turn at bay, when I saw a ledge on the

cliff above my head. There the cliff was deeply weathered, and the

branches pressed against it. A desperate scramble up the perilous

slant, and I had dragged my scratched and bruised body up on the ledge

and lay glaring down at my pursuers, who loaded the topmost branches

and howled up at me like lost souls. Evidently their climbing ability

did not include cliffs, because after one attempt, in which one sprang

up toward the ledge, clawed frantically for an instant on the sloping

stone wall, and then fell off with an awful shriek, they made no

effort to reach me.

Neither did they abandon their post. Stars came out, strange

unfamiliar constellations, that blazed whitely in the dark velvet

skies, and a broad golden moon rose above the cliffs, and flooded the

hills with weird light; but still my sentinels sat on the branches

below me and howled up at me their hatred and belly-hunger.

The air was icy, and frost formed on the bare stone where I lay. My

limbs became stiff and numb. I had knotted my girdle about my leg for

a tourniquet; the run had apparently ruptured some small veins laid

bare by the wound, because the blood flowed from it in an alarming

manner.

I never spent a more miserable night. I lay on the frosty stone

ledge, shaking with cold. Below me the eyes of my hunters burned up at

me. Throughout the shadowy hills sounded the roaring and bellowing of

unknown monsters. Howls, screams and yapping cut the night. And there

I lay, naked, wounded, freezing, hungry, terrified, just as one of my

remote ancestors might have lain in the Paleolithic Age of my own

planet.

I can understand why our heathen ancestors worshipped the sun. When

at last the cold moon sank and the sun of Almuric pushed its golden

rim above the distant cliffs, I could have wept for sheer joy. Below

me the hyenas snarled and stretched themselves, bayed up at me

briefly, and loped away in search of easier prey. Slowly the warmth of

the sun stole through my cramped, numbed limbs, and I rose stiffly up

to greet the day, just as that forgotten forbear of mine might have

stood up in the youthdawn of the Earth.

After a while I descended, and fell upon the nuts clustered in the

bushes near by. I was faint from hunger, and decided that I had as

soon die from poisoning as from starvation. I broke open the thick

shells and munched the meaty kernels eagerly, and I cannot recall any

Earthly meal, howsoever elaborate, that tasted half as good. No ill

effects followed; the nuts were good and nutritious. I was beginning

to overcome my surroundings, at least so far as food was concerned. I

had surmounted one obstacle of life on Almuric.

It is needless for me to narrate the details of the following

months. I dwelt among the hills in such suffering and peril as no man

on Earth has experienced for thousands of years. I make bold to say

that only a man of extraordinary strength and ruggedness could have

survived as I did. I did more than survive. I came at last to thrive

on the existence.

At first I dared not leave the valley, where I was sure of food and

water. I built a sort of nest of branches and leaves on the ledge, and

slept there at night. Slept? The word is misleading. I crouched there,

trying to keep from freezing, grimly lasting out the night. In the

daytime I snatched naps, learning to sleep anywhere, or at any time,

and so lightly that the slightest unusual noise would awaken me. The

rest of the time I explored my valley and the hills about, and picked

and ate nuts. Nor were my humble explorations uneventful. Time and

again I raced for the cliffs or the trees, winning sometimes by

shuddering hairbreadths. The hills swarmed with beasts, and all seemed

predatory.

It was that fact which held me to my valley, where I at least had a

bit of safety. What drove me forth at last was the same reason that

has always driven forth the human race, from the first apeman down to

the last European colonist—the search for food. My supply of nuts

became exhausted. The trees were stripped. This was not altogether on

my account, although I developed a most ravenous hunger, what of my

constant exertions; but others came to eat the nuts—huge shaggy

bearlike creatures, and things that looked like fur-clad baboons.

These animals ate nuts, but they were omnivorous, to judge by the

attention they accorded me. The bears were comparatively easy to

avoid; they were mountains of flesh and muscle, but they could not

climb, and their eyes were none too good. It was the baboons I learned

to fear and hate. They pursued me on sight, they could both run and

climb, and they were not balked by the cliff.

One pursued me to my eyrie, and swarmed up onto the ledge with me.

At least such was his intention, but man is always most dangerous when

cornered. I was weary of being hunted. As the frothing apish

monstrosity hauled himself up over my ledge, manlike, I drove my

poniard down between his shoulders with such fury that I literally

pinned him to the ledge; the keen point sinking a full inch into the

solid stone beneath him.

The incident showed me both the temper of my steel, and the growing

quality of my own muscles. I who had been among the strongest on my

own planet, found myself a weakling on primordial Almuric. Yet the

potentiality of mastery was in my brain and my thews, and I was

beginning to find myself.

Since survival was dependent on toughening, I toughened. My skin,

burnt brown by the sun and hardened by the elements, became more

impervious to both heat and cold than I had deemed possible. Muscles I

had not known I possessed became evident. Such strength and suppleness

became mine as Earthmen have not known for ages.

A short time before I had been transported from my native planet, a

noted physical culture expert had pronounced me the most perfectly

developed man on Earth. As I hardened with my fierce life on Almuric,

I realized that the expert honestly had not known what physical

development was. Nor had I. Had it been possible to divide my being

and set opposite each other the man that expert praised, and the man I

had become, the former would have seemed ridiculously soft, sluggish

and clumsy in comparison to the brown, sinewy giant opposed to him.

I no longer turned blue with the cold at night, nor did the rockiest

way bruise my naked feet. I could swarm up an almost sheer cliff with

the ease of a monkey, I could run for hours without exhaustion; in

short dashes it would have taken a racehorse to outfoot me. My wounds,

untended except for washing in cold water, healed of themselves, as

Nature is prone to heal the hurts of such as live close to her.

All this I narrate in order that it may be seen what sort of a man

was formed in the savage mold. Had it not been for the fierce forging

that made me steel and rawhide, I could not have survived the grim

bloody episodes through which I was to pass on that wild planet.

With new realization of power came confidence. I stood on my feet

and stared at my bestial neighbors with defiance. I no longer fled

from a frothing, champing baboon. With them, at least, I declared

feud, growing to hate the abominable beasts as I might have hated

human enemies. Besides, they ate the nuts I wished for myself.

They soon learned not to follow me to my eyrie, and the day

Comments (0)