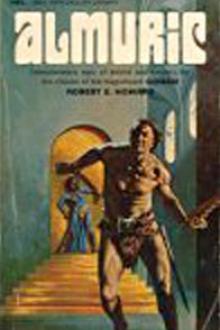

Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Robert E. Howard

- Performer: -

Book online «Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗». Author Robert E. Howard

when I dared to meet one on even terms, I will never forget the sight

of him frothing and roaring as he charged out of a clump of bushes,

and the awful glare in his manlike eyes. My resolution wavered, but it

was too late to retreat, and I met him squarely, skewering him through

the heart as he closed in with his long clutching arms.

But there were other beasts which frequented the valley, and which I

did not attempt to meet on any terms: the hyenas, the sabertooth

leopards, longer and heavier than an Earthly tiger and more ferocious;

giant mooselike creatures, carnivorous, with alligator-like tusks; the

monstrous bears; gigantic boars, with bristly hair which looked

impervious to a swordcut. There were other monsters, which appeared

only at night, and the details of which I was not able to make out.

These mysterious beasts moved mostly in silence, though some emitted

high-pitched weird wails, or low Earth-shaking rumbles. As the unknown

is most menacing, I had a feeling that these nighted monsters were

even more terrible than the familiar horrors which harried my day-life.

I remember one occasion on which I awoke suddenly and found myself

lying tensely on my ledge, my ears strained to a night suddenly and

breathlessly silent. The moon had set and the valley was veiled in

darkness. Not a chattering baboon, not a yelping hyena disturbed the

sinister stillness. Something was moving through the valley; I heard

the faint rhythmic swishing of the grass that marked the passing of

some huge body, but in the darkness I made out only a dim gigantic

shape, which somehow seemed infinitely longer than it was broad—out

of natural proportion, somehow. It passed away up the valley, and with

its going, it was as if the night audibly expelled a gusty sigh of

relief. The nocturnal noises started up again, and I lay back to sleep

once more with a vague feeling that some grisly horror had passed me

in the night.

I have said that I strove with the baboons over the possession of

the life-giving nuts. What of my own appetite and those of the beasts,

there came a time when I was forced to leave my valley and seek far

afield in search of nutriment. My explorations had become broader and

broader, until I had exhausted the resources of the country close

about. So I set forth at random through the hills in a southerly and

easterly direction. Of my wanderings I will deal briefly. For many

weeks I roamed through the hills, starving, feasting, threatened by

savage beasts sleeping in trees or perilously on tall rocks when night

fell. I fled, I fought, I slew, I suffered wounds. Oh, I can tell you

my life was neither dull nor uneventful.

I was living the life of the most primitive savage; I had neither

companionship, books, clothing, nor any of the things which go to make

up civilization. According to the cultured viewpoint, I should have

been most miserable. I was not. I revelled in my existence. My being

grew and expanded. I tell you, the natural life of mankind is a grim

battle for existence against the forces of nature, and any other form

of life is artificial and without realistic meaning.

My life was not empty; it was crowded with adventures calling on

every ounce of intelligence and physical power. When I swung down from

my chosen eyrie at dawn, I knew that I would see the sun set only

through my personal craft and strength and speed. I came to read the

meaning of every waving grass tuft, each masking bush, each towering

boulder. On every hand lurked Death in a thousand forms. My vigilance

could not be relaxed, even in sleep. When I closed my eyes at night it

was with no assurance that I would open them at dawn. I was fully

alive. That phrase has more meaning than appears on the surface. The

average civilized man is never fully alive; he is burdened with masses

of atrophied tissue and useless matter. Life flickers feebly in him;

his senses are dull and torpid. In developing his intellect he has

sacrificed far more than he realizes.

I realized that I, too, had been partly dead on my native planet.

But now I was alive in every sense of the word; I tingled and burned

and stung with life to the finger tips and the ends of my toes. Every

sinew, vein, and springy bone was vibrant with the dynamic flood of

singing, pulsing, humming life. My time was too much occupied with

food-getting and preserving my skin to allow the developing of the

morbid and intricate complexes and inhibitions which torment the

civilized individual. To those highly complex persons who would

complain that the psychology of such a life is over-simple, I can but

reply that in my life at that time, violent and continual action and

the necessity of action crowded out most of the gropings and

soul-searchings common to those whose safety and daily meals are assured

them by the toil of others. My life was primitively simple; I dwelt

altogether in the present. My life on Earth already seemed like a

dream, dim and far away.

All my life I had held down my instincts, had chained and enthralled

my over-abundant vitalities. Now I was free to hurl all my mental and

physical powers into the untamed struggle for existence, and I knew

such zest and freedom as I had never dreamed of.

In all my wanderings—and since leaving the valley I had covered an

enormous distance—I had seen no sign of humanity, or anything

remotely resembling humanity.

It was the day I glimpsed a vista of rolling grassland beyond the

peaks, that I suddenly encountered a human being. The meeting was

unexpected. As I strode along an upland plateau, thickly grown with

bushes and littered with boulders, I came abruptly on a scene striking

in its primordial significance.

Ahead of me the Earth sloped down to form a shallow bowl, the floor

of which was thickly grown with tall grass, indicating the presence of

a spring. In the midst of this bowl a figure similar to the one I had

encountered on my arrival on Almuric was waging an unequal battle with

a sabertooth leopard. I stared in amazement, for I had not supposed

that any human could stand before the great cat and live.

Always the glittering wheel of a sword shimmered between the monster

and its prey, and blood on the spotted hide showed that the blade had

been fleshed more than once. But it could not last; at any instant I

expected to see the swordsman go down beneath the giant body.

Even with the thought, I was running fleetly down the shallow slope.

I owed nothing to the unknown man, but his valiant battle stirred

newly plumbed depths in my soul. I did not shout but rushed in

silently and murderously, my poniard gleaming in my hand. Even as I

reached them, the great cat sprang, the sword went spinning from the

wielder’s hand, and he went down beneath the hurtling bulk. And almost

simultaneously I disembowled the sabertooth with one tremendous

ripping stroke.

With a scream it lurched off its victim, slashing murderously as I

leaped back, and then it began rolling and tumbling over the grass,

roaring hideously and ripping up the Earth with its frantic talons, in

a ghastly welter of blood and streaming entrails.

It was a sight to sicken the hardiest, and I was glad when the

mangled beast stiffened convulsively and lay still.

I turned to the man, but with little hope of finding life in him. I

had seen the terrible saberlike fangs of the giant carnivore tear into

his throat as he went down.

He was lying in a wide pool of blood, his throat horribly mangled. I

could see the pulsing of the great jugular vein which had been laid

bare, though not severed. One of the huge taloned paws had raked down

his side from arm-pit to hip, and his thigh had been laid open in a

frightful manner; I could see the naked bone, and from the ruptured

veins blood was gushing. Yet to my amazement the man was not only

living, but conscious. Yet even as I looked, his eyes glazed and the

light faded in them.

I tore a strip from his loincloth and made a tourniquet about his

thigh which somewhat slackened the flow of blood; then I looked down

at him helplessly. He was apparently dying, though I knew something of

the stamina and vitality of the wild and its people. And such

evidently this man was; he was as savage and hairy in appearance,

though not quite so bulky, as the man I had fought during my first day

on Almuric.

As I stood there helplessly, something whistled venomously past my

ear and thudded into the slope behind me. I saw a long arrow quivering

there, and a fierce shout reached my ears. Glaring about, I saw half a

dozen hairy men running fleetly toward me, fitting shafts to their

bows as they came.

With an instinctive snarl I bounded up the short slope, the whistle

of the missiles about my head lending wings to my heels. I did not

stop, once I had gained the cover of the bushes surrounding the bowl,

but went straight on, wrathful and disgusted. Evidently men as well as

beasts were hostile on Almuric, and I would do well to avoid them in

the future.

Then I found my anger submerged in a fantastic problem. I had

understood some of the shouts of the men as they rushed toward me. The

words had been in English, just as the antagonist of my first

encounter had spoken and understood that language. In vain I cudgeled

my mind for a solution. I had found that while animate and inanimate

objects on Almuric often closely copied things on Earth, yet there was

almost a striking difference somewhere, in substance, quality, shape

or mode of action. It was preposterous that certain conditions on the

separate planets could run such a perfect parallel as to produce an

identical language. Yet I could not doubt the evidence of my ears.

With a curse I abandoned the problem as too fantastic to waste time

on.

Perhaps it was this incident, perhaps the glimpse of the distant

savannas, which filled me with a restlessness and distaste for the

barren hill country where I had fared so hardily. The sight of men,

strange and alien as they were, stirred in my breast a desire for

human companionship, and this frustrated longing became in turn a

sudden feeling of repulsion for my surroundings. I did not hope to

meet friendly humans on the plains; but I determined to try my chances

upon them, nevertheless, though what perils I might meet there I could

not know. Before I left the hills some whim caused me to scrape from

my face my heavy growth and trim my shaggy hair with my poniard, which

had lost none of its razor edge. Why I did this I cannot say, unless

it was the natural instinct of a man setting forth into new country to

look his “best.”

The next morning I descended into the grassy plains, which swept

eastward and southward as far as sight could reach. I continued

eastward and covered many miles that day, without any unusual

incident. I encountered several small winding rivers, along whose

margins the grass stood taller than my head. Among this grass I heard

the snorting and thrashing of heavy animals of some sort, and gave

them a wide berth—for which caution I was later thankful.

The rivers were thronged in

Comments (0)