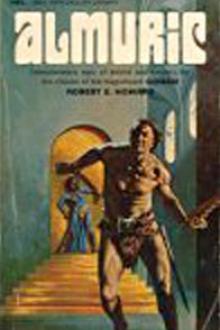

Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Robert E. Howard

- Performer: -

Book online «Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗». Author Robert E. Howard

rest of our women.”

“You mean all the women look like her, and all the men look like

you?”

“Certainly—allowing for their individual characteristics. Is it

otherwise among your people? That is, if you are not a solitary

freak.”

“Well, I’ll be—” I began in bewilderment, when another warrior

appeared in the door, saying.

“I’m to relieve you, Thab. The warriors

have decide to leave the matter to Khossuth when he returns on the

morrow.”

Thab departed and the other seated himself on the bench. I made no

attempt to talk to him. My head was swimming with the contradictory

phenomena I had heard and observed, and I felt the need of sleep. I

soon sank into dreamless slumber.

Doubtless my wits were still addled from the battering I had

received. Otherwise I would have snapped awake when I felt something

touch my hair. As it was, I woke only partly. From under drooping lids

I glimpsed, as in a dream, a girlish face bent close to mine, dark

eyes wide with frightened fascination, red lips parted. The fragrance

of her foamy black hair was in my nostrils. She timidly touched my

face, then drew back with a quick soft intake of breath, as if

frightened by her action. The guard snored on the bench. The torch had

burned to a stub that cast a weird dull glow over the chamber.

Outside, the moon had set. This much I vaguely realized before I sank

back into slumber again, to be haunted by a dim beautiful face that

shimmered through my dreams.

I Awoke Again in the cold gray light of dawn, at a time when the

condemned meet their executioners. A group of men stood over me, and

one I knew was Khossuth the Skullsplitter.

He was taller than most, and leaner—almost gaunt in comparison to

the others. This circumstance made his broad shoulders seem abnormally

huge. His face and body were seamed with old scars. He was very dark,

and apparently old; an impressive and terrible image of somber

savagery.

He stood looking down at me, fingering the hilt of his great sword.

His gaze was gloomy and detached.

“They say you claim to have beaten Logar of Thurga in open fight,”

he said at last, and his voice was cavernous and ghostly in a manner I

cannot describe.

I did not reply, but lay staring up at him, partly in fascination at

his strange and menacing appearance, partly in the anger that seemed

generally to be with me during those times.

“Why do you not answer?” he rumbled.

“Because I’m weary of being called a liar,” I snarled.

“Why did you come to Koth?”

“Because I was tired of living alone among wild beasts. I was a

fool. I thought I would find human beings whose company was preferable

to the leopards and baboons. I find I was wrong.”

He tugged his bristling mustaches.

“Men say you fight like a mad leopard. Thab says that you did not

come to the gates as an enemy comes. I love brave men. But what can we

do? If we free you, you will hate us because of what has passed, and

your hate is not lightly to be loosed.”

“Why not take me into the tribe?” I remarked, at random.

He shook his head. “We are not Yagas, to keep slaves.”

“Nor am I a slave,” I grunted. “Let me live among you as an equal. I

will hunt and fight with you. I am as good a man as any of your

warriors.”

At this another pushed past Khossuth. This fellow was bigger than

any I had yet seen in Koth—not taller, but broader, more massive. His

hair was thicker on his limbs, and of a peculiar rusty cast instead of

black.

“That you must prove!” he roared, with an oath. “Loose him,

Khossuth! The warriors have been praising his power until my belly

revolts! Loose him and let us have a grapple!”

“The man is wounded, Ghor,” answered Khossuth.

“Then let him be cared for until his wound is healed,” urged the

warrior eagerly, spreading his arms in a curious grappling gesture.

“His fists are like hammers,” warned another.

“Thak’s devils!” roared Ghor, his eyes glaring, his hairy arms

brandished. “Admit him into the tribe, Khossuth! Let him endure the

test! If he survives—well, by Thak, he’ll be worthy even to be called

a man of Koth!”

“I will go and think upon the matter,” answered Khossuth after a

long deliberation.

That settled the matter for the time being. All trooped out after

him. Thab was last, and at the door he turned and made a gesture which

I took to be one of encouragement. These strange people seemed not

entirely without feelings of pity and friendship.

The day passed uneventfully. Thab did not return. Other warriors

brought me food and drink, and I allowed them to bandage my scalp.

With more human treatment the wild-beast fury in me had been

subordinated to my human reason. But that fury lurked close to the

surface of my soul, ready to blaze into ferocious life at the

slightest encroachment.

I did not see the girl Altha, though I heard light footsteps outside

the chamber several times, whether hers or another’s I could not know.

About nightfall a group of warriors came into the room and announced

that I was to be taken to the council, where Khossuth would listen to

all arguments and decide my fate. I was surprised to learn that

arguments would be presented on my behalf. They got my promise not to

attack them, and loosed me from the chain that bound me to the wall,

but they did not remove the shackles on my wrists and ankles.

I was escorted out of the chamber into a vast hall, lighted by white

fire torches. There were no hangings or furnishings, nor any sort of

ornamentation—just an almost oppressive sense of massive

architecture.

We traversed several halls, all equally huge and windy, with rugged

walls and lofty ceilings, and came at last into a vast circular space,

roofed with a dome. Against the back wall a stone throne stood on a

block-like dais, and on the throne sat old Khossuth in gloomy majesty,

clad in a spotted leopardskin. Before him in a vast three-quarters

circle sat the tribe, the men cross-legged on skins spread on the

stone floor, and behind them the women and children seated on

fur-covered benches.

It was a strange concourse. The contrast was startling between the

hairy males and the slender, white-skinned, dainty women. The men were

clad in loincloths and high-strapped sandals; some had thrown

pantherskins over their massive shoulders. The women were dressed

similar to the girl Altha, whom I saw sitting with the others. They

wore soft sandals or none, and scanty tunics girdled about their

waists. That was all. The difference of the sexes was carried out down

to the smallest babies. The girl children were quiet, dainty and

pretty. The young males looked even more like monkeys than did their

elders.

I was told to take my seat on a block of stone in front and somewhat

to the side of the dais. Sitting among the warriors I saw Ghor,

squirming impatiently as he unconsciously flexed his thick biceps.

As soon as I had taken my seat, the proceedings went forward.

Khossuth simply announced that he would hear the arguments, and

pointed out a man to represent me, at which I was again surprised, but

this apparently was a regular custom among these people. The man

chosen was the lesser chief who had commanded the warriors I had

battled in the cell, and they called him Gutchluk Tigerwrath. He eyed

me venemously as he limped forward with no great enthusiasm, bearing

the marks of our encounter.

He laid his sword and dagger on the dais, and the foremost warriors

did likewise. Then he glared at the rest truculently, and Khossuth

called for arguments to show why Esau Cairn—he made a marvelous

jumble of the pronunciation—should not be taken into the tribe.

Apparently the reasons were legion. Half a dozen warriors sprang up

and began shouting at the top of their voice, while Gutchluk dutifully

strove to answer them. I felt already doomed. But the game was not

played out, or even well begun. At first Gutchluk went at it only

half-heartedly, but opposition heated him to his talk. His eyes

blazed, his jaw jutted, and he began to roar and bellow with the best

of them. From the arguments he presented, or rather thundered, one

would have thought he and I were lifelong friends.

No particular person was designated to protest against me. Everybody

who wished took a hand. And if Gutchluk won over anyone, that person

joined his voice to Gutchluk’s. Already there were men on my side.

Thab’s shout and Ghor’s bellow vied with my attorney’s roar, and soon

others took up my defense.

That debate is impossible for an Earthman to conceive of, without

having witnessed it. It was sheer bedlam, with from three voices to

five hundred voices clamoring at once. How Khossuth sifted any sense

out of it, I cannot even guess. But he brooded somberly above the

tumult, like a grim god over the paltry aspirations of mankind.

There was wisdom in the discarding of weapons. Dispute frequently

became biting, and criticisms of ancestors and personal habits entered

into it. Hands clutched at empty belts and mustaches bristled

belligerently. Occasionally Khossuth lifted his weird voice across the

clamor and restored a semblance of order.

My attempts to follow the arguments were vain. My opponents went

into matters seemingly utterly irrelevant, and were met by rebuttals

just as illogical. Authorities of antiquity were dragged out, to be

refuted by records equally musty.

To further complicate matters, disputants frequently snared

themselves in their own arguments, or forgot which side they were on,

and found themselves raging frenziedly on the other. There seemed no

end to the debate, and no limit to the endurance of the debaters. At

midnight they were still yelling as loudly, and shaking their fists in

one another’s beards as violently as ever.

The women took no part in the arguments.

They began to glide away about midnight, with the children. Finally

only one small figure was left among the benches. It was Altha, who

was following—or trying to follow—the proceedings with a surprising

interest.

I had long since given up the attempt. Gutchluk was holding the

floor valiantly, his veins swelling and his hair and beard bristling

with his exertions. Ghor was actually weeping with rage and begging

Khossuth to let him break a few necks. Oh, that he had lived to see

the men of Koth become adders and snakes, with the hearts of buzzards

and the guts of toads! he bawled, brandishing his huge arms to high

heaven.

It was all a senseless madhouse to me. Finally, in spite of the

clamor, and the fact that my life was being weighed in the balance, I

fell asleep on my block and snored peacefully while the men of Koth

raged and pounded their hairy breasts and bellowed, and the strange

planet of Almuric whirled on its way under the stars that neither knew

nor cared for men, Earthly or otherwise.

It was dawn when Thab shook me awake and shouted in my ear: “We have

won! You enter the tribe, if you’ll wrestle Ghor!”

“I’ll break his back!” I grunted, and went back to sleep again.

So began my life as a man among men on Almuric. I who had begun

Comments (0)