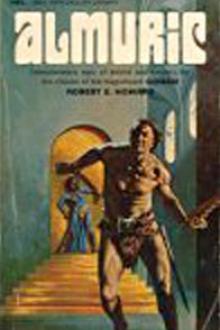

Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗

- Author: Robert E. Howard

- Performer: -

Book online «Almuric, Robert E. Howard [love books to read .txt] 📗». Author Robert E. Howard

Almuric

by Robert E. Howard

First published in 1939, copyright unrenewed.

Foreword

It was not my original intention ever to divulge the whereabouts of

Esau Cairn, or the mystery surrounding him. My change of mind was

brought about by Cairn himself, who retained a perhaps natural and

human desire to give his strange story to the world which had disowned

him and whose members can now never reach him. What he wishes to tell

is his affair. One phase of my part of the transaction I refuse to

divulge; I will not make public the means by which I transported Esau

Cairn from his native Earth to a planet in a solar system undreamed of

by even the wildest astronomical theorists. Nor will I divulge by what

means I later achieved communication with him, and heard his story

from his own lips, whispering ghostily across the cosmos.

Let me say that it was not premeditated. I stumbled upon the Great

Secret quite by accident in the midst of a scientific experiment, and

never thought of putting it to any practical use, until that night

when Esau Cairn groped his way into my darkened observatory, a hunted

man, with the blood of a human being on his hands. It was chance led

him there, the blind instinct of the hunted thing to find a den

wherein to turn at bay.

Let me state definitely and flatly, that, whatever the appearances

against him, Esau Cairn is not, and was never, a criminal. In that

specific case he was merely the pawn of a corrupt political machine

which turned on him when he realized his position and refused to

comply further with its demands. In general, the acts of his life

which might suggest a violent and unruly nature simply sprang from his

peculiar mental make-up.

Science is at last beginning to perceive that there is sound truth

in the popular phrase, “born out of his time.” Certain natures are

attuned to certain phases or epochs of history, and these natures,

when cast by chance into an age alien to their reactions and emotions,

find difficulty in adapting themselves to their surroundings. It is

but another example of nature’s inscrutable laws, which sometimes are

thrown out of stride by some cosmic friction or rift, and result in

havoc to the individual and the mass.

Many men are born outside their century; Esau Cairn was born outside

his epoch. Neither a moron nor a low-class primitive, possessing a

mind well above the average, he was, nevertheless, distinctly out of

place in the modern age. I never knew a man of intelligence so little

fitted for adjustment in a machine-made civilization. (Let it be noted

that I speak of him in the past tense; Esau Cairn lives, as far as the

cosmos is concerned; as far as the Earth is concerned, he is dead, for

he will never again set foot upon it.)

He was of a restless mold, impatient of restraint and resentful of

authority. Not by any means a bully, he at the same time refused to

countenance what he considered to be the slightest infringement on his

rights. He was primitive in his passions, with a gusty temper and a

courage inferior to none on this planet. His life was a series of

repressions. Even in athletic contests he was forced to hold himself

in, lest he injure his opponents. Esau Cairn was, in short, a freak—a

man whose physical body and mental bent leaned back to the primordial.

Born in the Southwest, of old frontier stock, he came of a race

whose characteristics were inclined toward violence, and whose

traditions were of war and feud and battle against man and nature. The

mountain country in which he spent his boyhood carried out the

tradition. Contest—physical contest—was the breath of life to him.

Without it he was unstable and uncertain. Because of his peculiar

physical make-up, full enjoyment in a legitimate way, in the ring or

on the football field was denied him. His career as a football player

was marked by crippling injuries received by men playing against him,

and he was branded as an unnecessarily brutal man, who fought to maim

his opponents rather than win games. This was unfair. The injuries

were simply resultant from the use of his great strength, always so

far superior to that of the men opposed to him. Cairn was not a great

sluggish lethargic giant as so many powerful men are; he was vibrant

with fierce life, ablaze with dynamic energy. Carried away by the lust

of combat, he forgot to control his powers, and the result was broken

limbs or fractured skulls for his opponents.

It was for this reason that he withdrew from college life,

unsatisfied and embittered, and entered the professional ring. Again

his fate dogged him. In his training-quarters, before he had had a

single match, he almost fatally injured a sparring partner. Instantly

the papers pounced upon the incident, and played it up beyond its

natural proportions. As a result Cairn’s license was revoked.

Bewildered, unsatisfied, he wandered over the world, a restless

Hercules, seeking outlet for the immense vitality that surged

tumultuously within him, searching vainly for some form of life wild

and strenuous enough to satisfy his cravings, born in the dim red days

of the world’s youth.

Of the final burst of blind passion that banished him for ever from

the life wherein he roamed, a stranger, I need say little. It was a

nine-days’ wonder, and the papers exploited it with screaming

headlines. It was an old story—a rotten city government, a crooked

political boss, a man chosen, unwittingly on his part, to be used as a

tool and serve as a puppet.

Cairn, restless, weary of the monotony of a life for which he was

unsuited, was an ideal tool—for a while. But Cairn was neither a

criminal nor a fool. He understood their game quicker than they

expected, and took a stand surprisingly firm to them, who did not know

the real man.

Yet, even so, the result would not have been so violent if the man

who had used and ruined Cairn had any real intelligence. Used to

grinding men under his feet and seeing them cringe and beg for mercy,

Boss Blaine could not understand that he was dealing with a man to

whom his power and wealth meant nothing. Yet so schooled was Cairn to

iron self-control that it required first a gross insult, then an actual

blow on the part of Blaine, to rouse him. Then for the first time in

his life, his wild nature blazed into full being. All his thwarted and

repressed life surged up behind the clenched fist that broke Blaine’s

skull like an eggshell and stretched him lifeless on the floor, behind

the desk from which he had for years ruled a whole district.

Cairn was no fool. With the red haze of fury fading from his glare,

he realized that he could not hope to escape the vengeance of the

machine that controlled the city. It was not because of fear that he

fled Blaine’s house. It was simply because of his primitive instinct

to find a more convenient place to turn at bay and fight out his death

fight.

So it was that chance led him to my observatory.

He would have left, instantly, not wishing to embroil me in his

trouble, but I persuaded him to remain and tell me his story. I had

long expected some catastrophe of the sort. That he had repressed

himself as long as he did, shows something of his iron character. His

nature was as wild and untamed as that of a maned lion.

He had no plan—he simply intended to fortify himself somewhere and

fight it out with the police until he was riddled with lead.

I at first agreed with him, seeing no better alternative. I was not

so naive as to believe he had any chance in the courts with the

evidence that would be presented against him. Then a sudden thought

occurred to me, so fantastic and alien, and yet so logical, that I

instantly propounded it to my companion. I told him of the Great

Secret, and gave him proof of its possibilities.

In short, I urged him to take the chance of a flight through space,

rather than meet the certain death that awaited him.

And he agreed. There was no place in the universe which would

support human life. But I had looked beyond the knowledge of men, in

universes beyond universes. And I chose the only planet I knew on

which a human being could exist—the wild, primitive, and strange

planet I named Almuric.

Cairn understood the risks and uncertainties as well as I. But he

was utterly fearless—and the thing was done. Esau Cairn left the

planet of his birth, for a world swimming afar in space, alien, aloof,

strange.

Esau Cairn’s Narrative

The Transition was so swift and brief, that it seemed less than a

tick of time lay between the moment I placed myself in Professor

Hildebrand’s strange machine, and the instant when I found myself

standing upright in the clear sunlight that flooded a broad plain. I

could not doubt that I had indeed been transported to another world.

The landscape was not so grotesque and fantastic as I might have

supposed, but it was indisputably alien to anything existing on the

Earth.

But before I gave much heed to my surroundings, I examined my own

person to learn if I had survived that awful flight without injury.

Apparently I had. My various parts functioned with their accustomed

vigor. But I was naked. Hildebrand had told me that inorganic

substance could not survive the transmutation. Only vibrant, living

matter could pass unchanged through the unthinkable gulfs which lie

between the planets. I was grateful that I had not fallen into a land

of ice and snow. The plain seemed filled with a lazy summerlike heat.

The warmth of the sun was pleasant on my bare limbs.

On every side stretched away a vast level plain, thickly grown with

short green grass. In the distance this grass attained a greater

height, and through it I caught the glint of water. Here and there

throughout the plain this phenomenon was repeated, and I traced the

meandering course of several rivers, apparently of no great width.

Black dots moved through the grass near the rivers, but their nature I

could not determine. However, it was quite evident that my lot had not

been cast on an uninhabited planet, though I could not guess the

nature of the inhabitants. My imagination peopled the distances with

nightmare shapes.

It is an awesome sensation to be suddenly hurled from one’s native

world into a new strange alien sphere. To say that I was not appalled

at the prospect, that I did not shrink and shudder in spite of the

peaceful quiet of my environs, would be hypocrisy. I, who had never

known fear, was transformed into a mass of quivering, cowering nerves,

starting at my own shadow. It was that man’s utter helplessness was

borne in upon me, and my mighty frame and massive thews seemed frail

and brittle as the body of a child. How could I pit them against an

unknown

Comments (0)