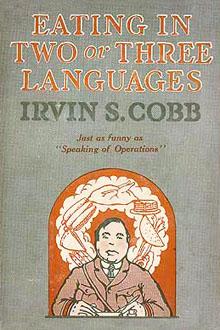

Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗

- Author: Irvin S. Cobb

- Performer: -

Book online «Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗». Author Irvin S. Cobb

I shall never forget the first meals I had on English soil, this latest trip. At the port where we landed, in the early afternoon of a raw day, you could get tea if you cared for tea, which I do not; but there was no sugar—only saccharine—to sweeten it with, and no rich cream, or even skim milk, available with which to dilute it. The accompanying buns had a flat, dry, floury taste, and the portions of butter served with them were very homoeopathic indeed as to size and very oleomargarinish as to flavour.

Going up to London we rode in a train that was crowded and darkened. Brilliantly illuminated trains scooting across country offered an excellent mark for the aim of hostile air raiders, you know; so in each compartment the gloom was enhanced rather than dissipated by two tiny pin points of a ghastly pale-blue gas flame. I do not know why there should have been two of these lights, unless it was that the second one was added so that by its wan flickerings you could see the first one, and vice versa.

During the trip, which lasted several hours longer than the scheduled running time, we had for refreshments a few gnarly apples, purchased at a way station; and that was all. Recalling the meals that formerly had been served aboard the boat trains of this road, I realised I was getting my preliminary dose of life on an island whose surrounding waters were pestered by U-boats and whose shipping was needed for transport service. But I pinned my gastronomic hopes on London, that city famed of old for the plenteous prodigality of its victualling facilities. In my ignorance I figured that the rigours of rationing could not affect London to any very noticeable extent. A little trimming down here and there, an enforced curtailment in this direction and that—yes, perhaps so; but surely nothing more serious.

Immediately on arrival we chartered a taxicab—a companion and I did. This was not so easy a job as might be imagined by one who formed his opinions on past recollections of London, because, since gasoline was carefully rationed there, taxis were scarce where once they had been numerous. Indeed, I know of no city in which, in antebellum days, taxis were so numerously distributed through almost every quarter of the town as in London. At any busy corner there were almost as many taxicabs waiting and ready to serve you as there are taxicabs in New York whose drivers are cruising about looking for a chance to run over you. The foregoing is still true of New York, but did not apply to London in war time.

Having chartered our cab, much to the chagrin of a group of our fellow travellers who had wasted precious time getting their heavy luggage out of the van, we rode through the darkened streets to a hotel formerly renowned for the scope and excellence of its cuisine. We reached there after the expiration of the hour set apart under the food regulations for serving dinner to the run of folks. But, because we were both in uniform—he as a surgeon in the British Army, and I as a correspondent—and because we had but newly finished a journey by rail, we were entitled, it seemed, to claim refreshment.

However, he, as an officer, was restricted to a meal costing not to exceed six shillings—and six shillings never did go far in this hotel, even when prices were normal. Not being an officer but merely a civilian disguised in the habiliments of a military man, I, on the other hand, was bound by no such limitations, but might go as far as I pleased. So it was decided that I should order double portions of everything and surreptitiously share with him; for by now we were hungry to the famishing point.

We had our minds set on a steak—a large thick steak served with onions, Desdemona style—that is to say, smothered. It was a pretty thought, a passing fair conception—but a vain one.

"No steaks to-night, sir," said the waiter sorrowfully.

"All right, then," one of us said. "How about chops—fat juicy chops?"

"Oh, no, sir; no chops, sir," he told us.

"Well then, what have you in the line of red meats?"

He was desolated to be compelled to inform us that there were no red meats of any sort to be had, but only sea foods. So we started in with oysters. Personally I have never cared deeply for the European oyster. In size he is anæmic and puny as compared with his brethren of the eastern coast of North America; and, moreover, chronically he is suffering from an acute attack of brass poisoning. The only way by which a novice may distinguish a bad European oyster from a good European oyster is by the fact that a bad one tastes slightly better than a good one does. In my own experience I have found this to be the one infallible test.

We had oysters until both of us were full of verdigris, and I, for one, had a tang in my mouth like an antique bronze jug; and then we proceeded to fish. We had fillets of sole, which tasted as they looked—flat and a bit flabby. Subsequently I learned that this lack of savour in what should be the most toothsome of all European fishes might be attributed to an insufficiency of fat in the cooking; but at the moment I could only believe the trip up from Dover had given the poor thing a touch of car sickness from which he had not recovered before he reached us.

After that we had lobsters, half-fare size, but charged for at the full adult rates. And, having by now exhausted our capacity for sea foods, we wound up with an alleged dessert in the shape of three drowned prunes apiece, the remains being partly immersed in a palish custardlike composition that was slightly sour.

"Never mind," I said to my indignant stomach as we left the table—"Never mind! I shall make it all up to you for this mistreatment at breakfast to-morrow morning. We shall rise early—you and I—and with loud gurgling cries we shall leap headlong into one of those regular breakfasts in which the people of this city and nation specialise so delightfully. Food regulators may work their ruthless will upon the dinner trimmings, but none would dare to put so much as the weight of one impious finger upon an Englishman's breakfast table to curtail its plenitude. Why, next to Magna Charta, an Englishman's breakfast is his most sacred right."

This in confidence was what I whispered to my gastric juices. You see, being still in ignorance of the full scope of the ration scheme in its application to the metropolitan district, and my disheartening experience at the meal just concluded to the contrary notwithstanding, I had my thoughts set upon rashers of crisp Wiltshire bacon, and broad segments of grilled York ham, and fried soles, and lovely plump sausages bursting from their jackets, and devilled kidneys paired off on a slice of toast, like Noah and his wife crossing the gangplank into the Ark.

Need I prolong the pain of my disclosures by longer withholding the distressing truth that breakfast next morning was a failure too? To begin with, I couldn't get any of those lovely crisp crescent rolls that accord so rhythmically with orange marmalade and strawberry jam. I couldn't get hot buttered toast either, but only some thin hard slabs of war bread, which seemingly had been dry-cured in a kiln. I could have but a very limited amount of sugar—a mere pinch, in fact; and if I used it to tone up my coffee there would be none left for oatmeal porridge. Moreover, this dab of sugar was to be my full day's allowance, it seemed. There was no cream for the porridge either, but, instead, a small measure of skimmed milk so pale in colour that it had the appearance of having been diluted with moonbeams.

Furthermore, I was informed that prior to nine-thirty I could have no meat of any sort, the only exceptions to this cruel rule being kippered herrings and bloaters; and in strict confidence the waiter warned me that, for some mysterious reason, neither the kippers nor the bloaters seemed to be up to their oldtime mark of excellence just now. From the same source I gathered that it would be highly inadvisable to order fried eggs, because of the lack of sufficient fat in which to cook them. So, as a last resort, I ordered two eggs, soft-boiled. They were served upended, English-fashion, in little individual cups, the theory being that in turn I should neatly scalp the top off of each egg with my spoon and then scoop out the contents from Nature's own container.

Now Englishmen are born with the faculty to perform this difficult achievement; they inherit it. But I have known only one American who could perform the feat with neatness and despatch; and, as he had devoted practically all his energies to mastering this difficult alien art, he couldn't do much of anything else, and, except when eggs were being served in the original packages, he was practically a total loss in society. He was a variation of the breed who devote their lives to producing a perfect salad dressing; and you must know what sad affairs those persons are when not engaged in following their lone talent. Take them off of salad dressings and they are just naturally null and void.

In my crude and amateurish way I attacked those eggs, breaking into them, not with the finesse the finished egg burglar would display, but more like a yeggman attacking a safe. I spilt a good deal of the insides of those eggs down over their outsides, producing a most untidy effect; and when I did succeed in excavating a spoonful I generally forgot to season it, or else it was full of bits of shell. Altogether, the results were unsatisfactory and mussy. Rarely have I eaten a breakfast which put so slight a subsequent strain upon my digestive processes.

Until noon I hung about, preoccupied and surcharged with inner yearnings. There were plenty of things—important things, too, they were—that I should have been doing; but I couldn't seem to fix my mind upon any subject except food. The stroke of midday found me briskly walking into a certain restaurant on the Strand that for many decades has been internationally famous for the quality and the unlimited quantity of its foods, and more particularly for its beef and its mutton. If ever you visited London in peacetime you must remember the place I mean.

The carvers were middle-aged full-ported men, with fine ruddy complexions, and moustaches of the Japanese weeping mulberry or mammoth droop variety. On signal one of them would come promptly to you where you sat, he shoving ahead of him a great trencher on wheels, with a spirit lamp blazing beneath the platter to keep its delectable burden properly hot. It might be that he brought to you a noble haunch of venison or a splendid roast of pork or a vast leg of boiled mutton; or, more likely yet, a huge joint

Comments (0)