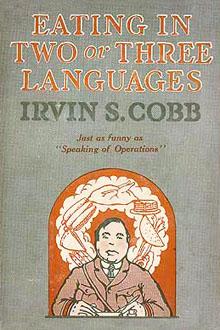

Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗

- Author: Irvin S. Cobb

- Performer: -

Book online «Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗». Author Irvin S. Cobb

At first, when we were green at the thing, we sometimes tried to interrogate the local gendarme; but complications, misunderstandings, and that same confusion of tongues which spoiled so promising a building project one time at the Tower of Babel always ensued. Central Europe has a very dense population, as the geographies used to tell us; but the densest ones get on the police force.

So when by bitter experience we had learned that the gendarme never by any chance could get our meaning and that we never could understand his gestures, we hit upon the wise expedient of going right away to the Last Chance for information.

At the outset I preferred to let one of my companions conduct the inquiry; but presently it dawned upon me that my mode of speech gave unbounded joy to my provincial audiences, and I decided that if a little exertion on my part brought a measure of innocent pleasure into the lives of these good folks it was my duty, as an Ally, to oblige whenever possible.

I came to realise that all these years I have been employing the wrong vehicle when I strive to dash off whimsicalities, because frequently my very best efforts, as done in English, have fallen flat. But when in some remote village I, using French, uttered the simplest and most commonplace remark to a French tavern keeper, with absolutely no intent or desire whatsoever, mind you, to be humorous or facetious, invariably he would burst instantly into peals of unbridled merriment.

Frequently he would call in his wife or some of his friends to help him laugh. And then, when his guffaws had died away into gentle chuckles, he would make answer; and if he spoke rapidly, as he always did, I would be swept away by the freshets of his eloquence and left gasping far beyond my depth.

That was why, when I went to a revue in Paris, I hoped they'd have some good tumbling on the bill.

I understand French, of course, curiously enough, but not as spoken. I likewise have difficulty in making out its meaning when I read it; but in other regards I flatter myself that my knowledge of the language is quite adequate. Certainly, as I have just stated, I managed to create a pleasant sensation among my French hearers when I employed it in conversation.

As I was saying, the general rule was that I should ask the name and whereabouts of a house in the town where we might procure victuals; and then, after a bit, when the laughing had died down, one of my companions would break in and find out what we wanted to know.

The information thus secured probably led us to a tiny cottage of mud-daubed wattles. Our hostess there might be a shapeless, wrinkled, clumsy old woman. Her kitchen equipment might be confined to an open fire and a spit, and a few battered pots.

Her larder might be most meagrely circumscribed as to variety, and generally was. But she could concoct such savoury dishes for us—such marvellous, golden-brown fried potatoes; such good soups; such savoury omelets; such toothsome fragrant stews! Especially such stews!

For all we knew—or cared—the meat she put into her pot might have been horse meat and the garnishments such green things as she had plucked at the roadside; but the flavour of the delectable broth cured us of any inclinations to make investigation as to the former stations in life of its basic constituents. I am satisfied that, chosen at random, almost any peasant housewife of France can take an old Palm Beach suit and a handful of potherbs and, mingling these together according to her own peculiar system, turn out a ragout fit for a king. Indeed, it would be far too good for some kings I know of.

And if she had a worn-out bath sponge and the cork of a discarded vanilla-extract bottle she, calling upon her hens for a little help in the matter of eggs, could produce for dessert a delicious meringue, with floating-island effects in it. I'd stake my life on her ability to deliver.

If, on such an occasion as the one I have sought to describe, we were perchance in the south of France or in the Côte-d'Or country, lying over toward the Swiss border, we could count upon having a bait of delicious strawberries to wind up with. But if perchance we had fared into one of the northeastern provinces we were reasonably certain the meal would be rounded out with helpings of a certain kind of cheese that is indigenous to those parts. It comes in a flat cake, which invariably is all caved in and squashed out, as though the cheese-maker had sat upon it while bringing it into the market in his two-wheeled cart.

Likewise, when its temperature goes up, it becomes more of a liquid than a solid; and it has an aroma by virtue of which it secures the attention and commands the respect of the most casual passer-by. It is more than just cheese. I should call it mother-of-cheese. It is to other and lesser cheeses as civet cats are to canary birds—if you get what I mean; and in its company the most boisterous Brie or the most vociferous Camembert you ever saw becomes at once deaf and dumb.

Its flavour is wonderful. Mainly it is found in ancient Normandy; and, among strangers, eating it—or, when it is in an especially fluid state, drinking it—comes under the head of outdoor sports. But the natives take it right into the same house with themselves.

And, no matter where we were—in Picardy, in Brittany, in the Vosges or the Champagne, as the case might be—we had wonderful crusty bread and delicious butter and a good light wine to go along with our meal. We would sit at a bare table in the smoky cluttered interior of the old kitchen, with the rafters just over our heads, and with the broken tiles—or sometimes the bare earthen floor—beneath our feet, and would eat our fill.

More times than once or twice or thrice I have known the mistress of the house at settlement time to insist that we were overpaying her. From a civilian compatriot she would have exacted the last sou of her just due; but, because we were Americans and because our country had sent its sons overseas to help her people save France, she, a representative of the most canny and thrifty class in a country known for the thriftiness of all its classes, hesitated to accept the full amount of the sum we offered her in payment.

She believed us, of course, to be rich—in the eyes of the European peasant all Americans are rich—and she was poor and hard put to it to earn her living; but here was a chance for her to show in her own way a sense of what she, as a Frenchwoman, felt for America. Somehow, the more you see of the French, the less you care for the Germans.

Moving on up a few miles nearer the trenches, we would run into our own people; and then we were sure of a greeting, and a chair apiece and a tin plate and a tin cup apiece at an American mess. I have had chuck with privates and I have had chow with noncoms; I have had grub with company commanders and I have dined with generals—and always the meal was flavoured with the good, strong man-talk of the real he-American.

The food was of the best quality and there was plenty of it for all, and some to spare. One reason—among others—why the Yank fought so well was because he was so well fed between fights.

The very best meals I had while abroad were vouchsafed me during the three days I spent with a front-line regiment as a guest of the colonel of one of our negro out fits. To this colonel a French general, out of the goodness of his heart, had loaned his cook, a whiskered poilu, who, before he became a whiskered poilu, had been the chef in the castle of one of the richest men in Europe.

This genius cooked the midday meals and the dinners; but, because no Frenchman can understand why any one should require for breakfast anything more solid than a dry roll and a dab of honey, the preparation of the morning meal was intrusted to a Southern black boy, who, I may say, was a regular skillet hound. And this gifted youth wrestled with the matutinal ham and eggs and flipped the flapjacks for the headquarters mess.

On a full Southern breakfast and a wonderful French luncheon and dinner a grown man can get through the day very, very well indeed, as I bear witness.

Howsomever, as spring wore into summer and summer ran its course, I began to long with a constantly increasing longing for certain distinctive dishes to be found nowhere except in my native clime; brook trout, for example, and roasting ears, and—Oh, lots of things! So I came home to get them.

And, now that I've had them, I often catch myself in the act of thoughtfully dwelling upon the fond remembrances of those spicy fragrant stews eaten in peasant kitchens, and those army doughnuts, and those slices of bacon toasted at daybreak on the lids of mess kits in British dugouts.

I suppose they call contentment a jewel because it is so rare.

BY IRVIN S. COBB FICTION Those Times and These Local Color Old Judge Priest Fibble, D.D. Back Home The Escape of Mr. Trimm WIT AND HUMOR "Speaking of Operations—" Europe Revised Roughing It De Luxe Cobb's Bill of Fare Cobb's Anatomy MISCELLANY The Thunders of Silence "Speaking of Prussians—" Paths of Glory GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY NEW YORKEnd of Project Gutenberg's Eating in Two or Three Languages, by Irvin S. Cobb

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EATING IN TWO OR THREE LANGUAGES ***

***** This file should be named 18526-h.htm or 18526-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/1/8/5/2/18526/

Produced by Audrey Longhurst, Janet Blenkinship, Sankar

Viswanathan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

of Distributed Proofreaders Europe at http://dp.rastko.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the

Comments (0)