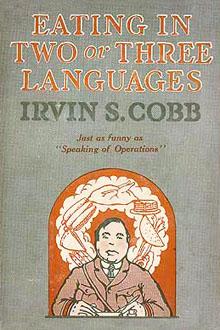

Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗

- Author: Irvin S. Cobb

- Performer: -

Book online «Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗». Author Irvin S. Cobb

Many's the hard battle that I had with these chaps in 1918. It never failed—not one single, solitary time did it fail—that the functionary who took my order first tried to tell me what my order was going to be, and then, after a struggle, reluctantly consented to bring me the things I wanted and insisted on having. Never once did he omit the ceremony of impressing it upon me that he would regard it as a deep favour if only I would be so good as to order a whole lobster. I do not think there was anything personal in this; he recommended the lobster because lobster was the most expensive thing he had in stock. If he could have thought of anything more expensive than lobster he would have recommended that.

I always refused—not that I harbour any grudge against lobsters as a class, but because I object to being dictated to by a buccaneer with flat feet, who wears a soiled dickey instead of a shirt, and who is only waiting for a chance to overcharge me or short-change me, or give me bad money, or something. If every other form of provender had failed them the populace of Paris could have subsisted very comfortably for several days on the lobsters I refused to buy in the course of the spring and summer of last year. I'm sure of it.

And when I had firmly, emphatically, yea, ofttimes passionately declined the proffered lobster, he, having with difficulty mastered his chagrin, would seek to direct my attention to the salmon, his motive for this change in tactics being that salmon, though apparently plentiful, was generally the second most expensive item upon the regular menu. Salmon as served in Paris wears a different aspect from the one commonly worn by it when it appears upon the table here.

Over there they cut the fish through amidships, in cross-sections, and, removing the segment of spinal column, spread the portion flat upon a plate and serve it thus; the result greatly resembling a pair of miniature pink horse collars. A man who knew not the salmon in his native state, or ordering salmon in France, would get the idea that the salmon was bowlegged and that the breast had been sold to some one else, leaving only the hind quarters for him.

Harking back to lobsters, I am reminded of a tragedy to which I was an eyewitness. Nearly every night for a week or more two of us dined at the same restaurant on the Rue de Rivoli. On the occasion of our first appearance here we were confronted as we entered by a large table bearing all manner of special delicacies and cold dishes. Right in the middle of the array was one of the largest lobsters I ever saw, reposing on a couch of water cress and seaweed, arranged upon a serviette. He made an impressive sight as he lay there prone upon his stomach, fidgeting his feelers in a petulant way.

We two took seats near by. At once the silent signal was given signifying, in the cipher code, "Americans in the house!" And the maître d'hôtel came to where he rested and, grasping him firmly just back of the armpits, picked him up and brought him over to us and invited us to consider his merits. When we had singly and together declined to consider the proposition of eating him in each of the three languages we knew—namely, English, bad French, and profane—the master sorrowfully returned him to his bed.

Presently two other Americans entered and immediately after them a party of English officers, and then some more Americans. Each time the boss would gather up the lobster and personally introduce him to the newcomers, just as he had done in our case, by poking the monster under their noses and making him wriggle to show that he was really alive and not operated by clockwork, and enthusiastically dilating upon his superior attractions, which, he assured them, would be enormously enhanced if only messieurs would agree forthwith to partake of him in a broiled state. But there were no takers; and so back again he would go to his place by the door, there to remain till the next prospective victim arrived.

We fell into the habit of going to this place in the evenings in order to enjoy repetitions of this performance while dining. The lobster became to us as an old friend, a familiar acquaintance. We took to calling him Jess Willard, partly on account of his reach and partly on account of his rugged appearance, but most of all because his manager appeared to have so much trouble in getting him matched with anybody.

HALF A DOZEN TIMES A NIGHT OR OFTENER HE TRAVELLED UNDER ESCORT THROUGH THE DINING ROOM

HALF A DOZEN TIMES A NIGHT OR OFTENER HE TRAVELLED UNDER ESCORT THROUGH THE DINING ROOM

Half a dozen times a night, or oftener, he travelled under escort through the dining room, always returning again to his regular station. Along about the middle of the week he began to fail visibly. Before our eyes we saw him fading. Either the artificial life he was leading or the strain of being turned down so often was telling upon him. It preyed upon his mind, as we could discern by his morose expression. It sapped his splendid vitality as well. No longer did he expand his chest and wave his numerous extremities about when being exhibited before the indifferent eyes of possible investors, but remained inert, logy, gloomy, spiritless—a melancholy spectacle indeed.

It now required artificial stimulation to induce him to display even a temporary interest in his surroundings. With a practised finger, his keeper would thump him on the tenderer portions of his stomach, and then he would wake up; but it was only for a moment. He relapsed again into his lamentable state of depression and languor. By every outward sign here was a lobster that fain would withdraw from the world. But we knew that for him there was no opportunity to do so; on the hoof he represented too many precious francs to be allowed to go into retirement.

Coming on Saturday night we realised that for our old friend the end was nigh. His eyes were deeply set about two-thirds of the way back toward his head and with one listless claw he picked at the serviette. The summons was very near; the dread inevitable impended.

Sunday night he was still present, but in a greatly altered state. During the preceding twenty-four hours his brave spirit had fled. They had boiled him then; so now, instead of being green, he was a bright and varnished red all over, the exact colour of Truck Six in the Paducah Fire Department.

We felt that we who had been sympathisers at the bedside during some of his farewell moments owed it to his memory to assist in the last sad rites. At a perfectly fabulous price we bought the departed and undertook to give him what might be called a personal interment; but he was a disappointment. He should have been allowed to take the veil before misanthropy had entirely undermined his health and destroyed his better nature, and made him, as it were, morbid. Like Harry Leon Wilson's immortal Cousin Egbert, he could be pushed just so far, and no farther.

Before I left Paris the city was put upon bread cards. The country at large was supposed to be on bread rations too; but in most of the smaller towns I visited the hotel keepers either did not know about the new regulation or chose to disregard it. Certainly they generally disregarded it so far as we were concerned. For all I know to the contrary, though, they were restricting their ordinary patrons to the ordained quantities and making an exception in the case of our people. It may have been one of their ways of showing a special courtesy to representatives of an allied race. It would have been characteristic of these kindly provincial innkeepers to have done just that thing.

Likewise, one could no longer obtain cheese in a first-grade Paris restaurant or aboard a French dining car, though cheese was to be had in unstinted quantity in the rural districts and in the Paris shops; and, I believe, it was also procurable in the cafés of the Parisian working classes, provided it formed a part of a meal costing not more than five francs, or some such sum. In a first-rate place it was, of course, impossible to get any sort of meal for five francs, or ten francs either; especially after the ten per cent luxury tax had been tacked on.

In March prices at the smarter café eating places had already advanced, I should say, at least one hundred per cent above the customary pre-war rates; and by midsummer the tariffs showed a second hundred per cent increase in delicacies, and one of at least fifty per cent in staples, which brought them almost up to the New York standards. Outside of Paris prices continued to be moderate and fair.

Just as I was about starting on my last trip to the Front before sailing for home, official announcement was made that dog biscuits would shortly be advanced in price to a well-nigh prohibitive figure. So I presume that very shortly thereafter the head waiters began offering dog biscuits to American guests. I knew they would do so, just as soon as a dog biscuit cost more than a lobster did.

Until this trip I never appreciated what a race of perfect cooks the French are. I thought I did, but I didn't. One visiting the big cities or stopping at show places and resorts along the main lines of motor and rail travel in peacetime could never come to a real and due appreciation of the uniformly high culinary expertness of the populace in general. I had to take campaigning trips across country into isolated districts lying well off the old tourist lanes to learn the lesson. Having learned it, I profited by it.

No matter how small the hamlet or how dingy appearing the so-called hotel in it might be, we were sure of getting satisfying food, cooked agreeably and served to us by a friendly, smiling little French maiden, and charged for at a most reasonable figure, considering that generally the town was fairly close up to the fighting lines and the bringing in of supplies for civilians' needs was frequently subordinated to the handling of military necessities.

Indeed, the place might be almost within range of the big guns and subjected to bombing outrages by enemy airmen, but somehow the local Boniface managed to produce food ample for our desires, and most appetising besides. His larder might be limited, but his good nature, like his willingness and his hospitality, was boundless.

I predict that there is going to be an era of better cooking in America before very long. Our soldiers, returning home, are going to demand a tastier and more diversified fare than many of them enjoyed before they put on khaki and went overseas; and they are going to get it, too. Remembering what they had to eat under French roofs, they will never again be satisfied with meats fried to death, with soggy vegetables, with underdone breads.

Sometimes as we went scouting about on our roving commission to see what we might see, at mealtime we would enter a community too small to harbour within it any establishment calling itself a hotel. In

Comments (0)