Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗

- Author: Irvin S. Cobb

- Performer: -

Book online «Eating in Two or Three Languages, Irvin S. Cobb [unputdownable books .TXT] 📗». Author Irvin S. Cobb

Project Gutenberg's Eating in Two or Three Languages, by Irvin S. Cobb

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

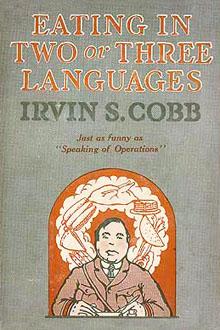

Title: Eating in Two or Three Languages

Author: Irvin S. Cobb

Release Date: June 7, 2006 [EBook #18526]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EATING IN TWO OR THREE LANGUAGES ***

Produced by Audrey Longhurst, Janet Blenkinship, Sankar

Viswanathan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

of Distributed Proofreaders Europe at http://dp.rastko.net

NO RED MEATS, BUT ONLY SEA FOODS

NO RED MEATS, BUT ONLY SEA FOODS

in Two or Three

Languages

By Irvin S. Cobb Author of

"Paths of Glory," "Those Times and These," etc.

New York George H. Doran Company

Copyright, 1919,

By George H. Doran Company

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY

TO B.B. McALPIN, ESQUIRE, WHO KNOWS A LOT ABOUT EATING ILLUSTRATIONS No Red Meats, but Only Sea Foods. Frontispiece Page "Herb, Stand Back! Stand Well Back to Avoid Being Splashed!" 14 Half a Dozen Times a Night or Oftener He Travelled under Escort through the Room 48 Eating in Two or Three Languages

On my way home from overseas I spent many happy hours mapping out a campaign. To myself I said: "The day I land is going to be a great day for some of the waiters and a hard day on some of the cooks. Persons who happen to be near by when I am wrestling with my first ear of green corn will think I am playing on a mouth organ. My behaviour in regard to hothouse asparagus will be reminiscent of the best work of the late Bosco. In the matter of cantaloupes I rather fancy I shall consume the first two on the half shell, or au naturel, as we veteran correspondents say; but the third one will contain about as much vanilla ice cream as you could put in a derby hat.

"And when, as I am turning over my second piece of fried chicken, with Virginia ham, if H. Hoover should crawl out from under it, and, shaking the gravy out of his eyes, should lift a warning hand, I shall say to him: 'Herb,' I shall say, 'Herb, stand back! Stand well back to avoid being splashed, Herb. Please desist and do not bother me now, for I am busy. Kindly remember that I am but just returned from over there and that for months and months past, as I went to and fro across the face of the next hemisphere that you'll run into on the left of you if you go just outside of Sandy Hook and take the first turn to the right, I have been storing up a great, unsatisfied longing for the special dishes of my own, my native land. Don't try, I pray you, to tell me a patriot can't do his bit and eat it too, for I know better.

"HERB, STAND BACK! STAND WELL BACK TO AVOID BEING SPLASHED!"

"HERB, STAND BACK! STAND WELL BACK TO AVOID BEING SPLASHED!"

"'Shortly I may be in a fitter frame of mind to listen to your admonitions touching on rationing schemes; but not to-day, and possibly not to-morrow either, Herb. At this moment I consider food regulations as having been made for slaves and perhaps for the run of other people; but not for me. As a matter of fact, what you may have observed up until now has merely been my preliminary attack—what you might call open warfare, with scouting operations. But when they bring on the transverse section of watermelon I shall take these two trenching tools which I now hold in my hands, and just naturally start digging in. I trust you may be hanging round then; you'll certainly overhear something.'

"'Kindly pass the ice water. That's it. Thank you. Join me, won't you, in a brimming beaker? It may interest you to know that I am now on my second carafe of this wholesome, delicious and satisfying beverage. Where I have lately been, in certain parts of the adjacent continent, there isn't any ice, and nobody by any chance ever drinks water. Nobody bathes in it either, so far as I have been able to note. You'll doubtless be interested in hearing what they do do with it over on that side. It took me months to find out.

"'Then finally, one night in a remote interior village, I went to an entertainment in a Y.M.C.A. hut. A local magician came out on the platform; and after he had done some tricks with cards and handkerchiefs which were so old that they were new all over again, he reached up under the tails of his dress coat and hauled out a big glass globe that was slopping full of its crystal-pure fluid contents, with a family of goldfish swimming round and round in it, as happy as you please.

"'So then, all in a flash, the answer came and I knew the secret of what the provincials in that section of Europe do with water. They loan it to magicians to keep goldfish in. But I prefer to drink a little of it while I am eating and to eat a good deal while I am drinking it; both of which, I may state, I am now doing to the best of my ability, and without let or hindrance, Herb.'"

To be exactly correct about it, I began mapping out this campaign long before I took ship for the homeward hike. The suggestion formed in my mind during those weeks I spent in London, when the resident population first went on the food-card system. You had to have a meat card, I think, to buy raw meat in a butcher shop, and you had to have another kind of meat card, I know, to get cooked meat in a restaurant; and you had to have a friend who was a smuggler or a hoarder to get an adequate supply of sugar under any circumstances. Before I left, every one was carrying round a sheaf of cards. You didn't dare go fishing if you had mislaid your worm card.

The resolution having formed, it budded and grew in my mind when I was up near the Front gallantly exposing myself to the sort of table-d'hôte dinners that were available then in some of the lesser towns immediately behind the firing lines; and it kept right on growing, so that by the time I was ready to sail it was full sized. En route, I thought up an interchangeable answer for two of the oldest conundrums of my childhood, one of them being: "Round as a biscuit, busy as a bee; busiest thing you ever did see," and the other, "Opens like a barn door, shuts like a trap; guess all day and you can't guess that." In the original versions the answer to the first was "A watch," and to the second, "A corset"—if I recall aright But the joint answer I worked out was as follows: "My face!"

Such was the pleasing program I figured out on shipboard. But, as is so frequently the case with the most pleasing things in life, I found the anticipation rather outshone the realisation. Already I detect myself, in a retrospective mood, hankering for the savoury ragoûts we used to get in peasant homes in obscure French villages, and for the meals they gave us at the regimental messes of our own forces, where the cooking was the home sort and good honest American slang abounded.

They called the corned beef Canned Willie; and the stew was known affectionately as Slum, and the doughnuts were Fried Holes. When the adjutant, who had been taking French lessons, remarked "What the la hell does that sacré-blew cook mean by serving forty-fours at every meal?" you gathered he was getting a mite tired of baked army beans. And if the lieutenant colonel asked you to pass him the Native Sons you knew he meant he wanted prunes. It was a great life, if you didn't weaken—and nobody did.

But, so far as the joys of the table are concerned, I think I shall be able to wait for quite a spell before I yearn for another whack at English eating. I opine Charles Dickens would be a most unhappy man could he but return to the scenes he loved and wrote about.

Dickens, as will be recalled, specialised in mouth-watering descriptions of good things and typically British things to eat—roast sucking pigs, with apples in their snouts; and baked goose; and suety plum puddings like speckled cannon balls; and cold game pies as big round as barrel tops—and all such. He wouldn't find these things prevailing to any noticeable extent in his native island now. Even the kidney, the same being the thing for which an Englishman mainly raises a sheep and which he always did know how to serve up better than any one else on earth, somehow doesn't seem to be the kidney it once upon a time was when it had the proper sorts of trimmings and sauces to go with it.

At this time England is no place for the epicure. In peacetime English cooks, as a rule, were not what you would call versatile; their range, as it were, was limited. Once, seeking to be blithesome and light of heart, I wrote an article in which I said there were only three dependable vegetables on the average Englishman's everyday menu—boiled potatoes, boiled cabbage, and a second helping of the boiled potatoes.

That was an error on my part; I was unintentionally guilty of the crime of underestimation. I should have added a fourth to the list of stand-bys—to wit: the vegetable marrow. For some reason, possibly because they are a stubborn and tenacious race, the English persist in looking upon the vegetable marrow as an object designed for human consumption, which is altogether the wrong view to take of it. As a foodstuff this article hasn't even the merit that attaches to stringy celery. You do not derive much nourishment from stale celery, but eating at it polishes the teeth and provides a healthful form of exercise that gives you an appetite for the rest of the meal.

From the vegetable marrow you derive no nourishment, and certainly you derive no exercise; for, being a soft, weak, spiritless thing, it offers no resistance whatever, and it looks a good deal like a streak of solidified fog and tastes like the place where an indisposed carrot spent the night. Next to our summer squash it is the feeblest imitation that ever masqueraded in a skin and called itself a vegetable. Yet its friends over there seem to set much store by it.

Likewise the English cook has always gone in rather extensively for boiling things. When in doubt she boiled. But it takes a lot of retouching to restore to a piece of boiled meat the juicy essences that have been simmered and drenched out of it. Since the English people, with such admirable English thoroughness, cut down on fats and oils and bacon garnishments, so that the greases might be conserved for the fighting forces; and since they have so largely had to do without imported spices and condiments, because the cargo spaces in the ships coming in were needed for military essentials, the boiled dishes of England appear to have lost most of their taste.

You can do a lot of browsing about at an English table these days and come

Comments (0)